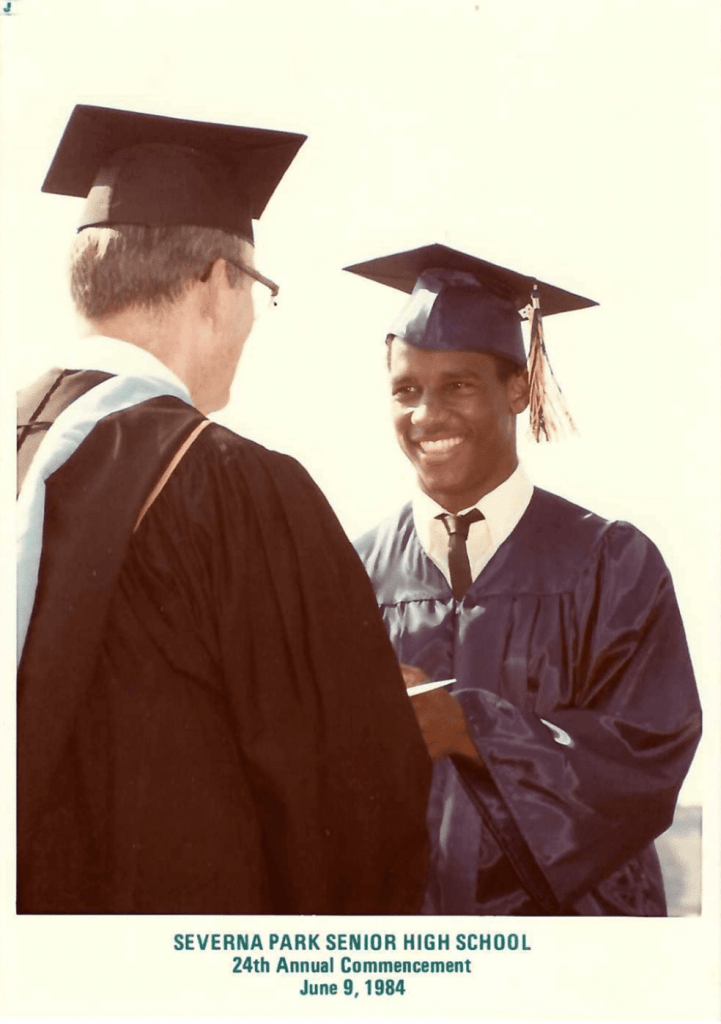

In the early 1980s, Alvin Bowman was a lacrosse prodigy at Severna Park High School, a dynasty that has captured more state championships than any school in Maryland history, before going on to an accomplished college career at Drexel University, where he was later inducted to the school’s athletic Hall of Fame as a member of its ‘80s All-Decade team.

Armed with an undergraduate business degree upon graduation and a welcoming, gregarious personality, he became a rising corporate star in the field of pharmaceutical sales.

But his recreational drug use, which started in college, eventually morphed into a debilitating crack addiction that nearly claimed his life.

This is the story of one person’s odyssey through the equal opportunity destroyer that is substance abuse, a man you may have encountered in the corridors of corporate America or seen panhandling and eating out of trash cans near Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

***

Temperatures dipped into the mid 30′s on the evening of November 17, 2022 as the championship game of the Maryland Masters Lacrosse League between the Rusty Cannons and Glyndon-SRLC got underway at Troy Park in Elkridge.

Alvin Bowman, once a lightning-fast, compact ball of muscle that wreaked havoc on opponents from his attack position in years past, doggedly chugged up and down the turf field.

56 years old at the time, he was far removed from his past days of dominance as one of the nation’s best players at Drexel University. Slim and spry then, now he’s slower and rounder around the midsection, with leg, neck and back injuries that compromised him throughout the season.

And he was happy, content to play the decoy in the 8-5 victory that earned the Cannons the title as Fall League Champions.

The joy was evident as he posed with the championship trophy, index finger pointing towards the sky.

The grin that stretched across his cherubic face, in and of itself, told a story. Yes, part of it was the proverbial thrill of victory.

There were also strains of hope in the unseen, of grim, shocking defeats and comebacks that took place far away from the athletic fields that once inspired and molded him, that harbored and nourished his dreams.

Bowman had his life back. He had lacrosse back.

Just a few years ago, that just didn’t seem possible.

***

On a Sunday morning in January 2009, Bowman’s soul was at ease as he pulled his spanking new white Nissan with slightly tinted windows into the parking lot of the Messiah Community Church in Owings Mills, Maryland, where pastor Rod Hairston, the Baltimore Ravens’ team chaplain at the time, delivered his sermons.

He promised his wife he’d be back home by 2 pm, but was suddenly overcome with an internal conflict that redirected him, not to his wife waiting for him at the home in Pasadena, Maryland they just had constructed, but to the streets of West Baltimore where his life had previously been completely demolished.

“I rolled up to a familiar spot, got one vial of crack, some weed and some Wild Irish Rose wine and tried to relax,” said Bowman. “But when I put one inside my body, I’ve never done just one. The next one is always right around the corner and then it’s off to the races. When that compulsion and obsession kicks in, I couldn’t stop no matter how much I wanted to.”

He’d been clean and sober for about eight months at that point.

On his way to the church service hours before relapsing, Bowman had a conversation with his sponsor, whom he always spoke with in the early morning after attending his 12-Step Recovery meetings. Once he settled in the church pew, he began listening to Hairston’s sermon, which focused on the disease of addiction.

Hairston, it seemed, was speaking directly to him as he quoted Proverbs 25:28, “A man without self-control is like a city broken into and left without walls” and Romans 5:3-5, “More than that, we rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not put us to shame…,”

Instead of feeling validated and encouraged for the mess he’d been able to climb out of – which included being shot in the leg in a drug deal gone bad, bouts of homelessness where he sometimes ate out of garbage cans, being viciously slashed with a box cutter by a dealer he once tried to scam, numerous arrests and stints in jail for drug possession, among others – Bowman had an entirely different reaction, one that he can’t readily explain.

It’s hard for him to reconcile how one minute, things felt so great. And the next, he was heading into the city towards those old haunts that he was so familiar with in search of crack cocaine.

Over the next six weeks or so, he wore those same church clothes and slept in his car, panhandling, and driving his vehicle as a hack.

For those who are unfamiliar, a “hack” is a Baltimore term for an illegal cab that poor folks in predominantly Black communities use to get around as an alternative to public transportation or not having debit or credit cards that can link to an Uber or Lyft account.

There’s a certain hand signal, an outstretched arm with two fingers extended as the wrist subtly shakes up and down, that people use to hail a hack.

The night before Valentine’s Day in 2009, six weeks into that drug binge after having bolted from the Owings Mills church service, Bowman would leave a friend’s place who lived in a row house on Preston Street, right off Martin Luther King Boulevard, at 1 a.m., disoriented from a bad batch of crack that was laced with speed. He was eager to track down some more vials for a better high.

Without any money, he turned to hacking.

He was driving down a desolate, dreary, ominous Park Heights Avenue toward the Mondawmin Mall. Bowman saw a guy shaking his wrist and wagging his fingers in need of a hack.

“I pulled over and he jumped into the passenger seat,” said Bowman. “He had on a nice, multi-colored jacket and said, ‘Turn here on Keyworth and go over to Reisterstown Road.’ He told me he was going to pick up his girlfriend and was then headed over to the East side. I’d already calculated how many crack vials the trip would be worth.”

When they arrived at his destination, Bowman was told to park by a salt box on a very dark street, the 3800 block of Towanda Avenue, that looked mostly abandoned.

The car was running and as soon as the passenger got out, there was a thumping bash at his driver’s side window.

“BANG!!!!!”

When he looked up, Bowman recalls seeing a tall man dressed in all black. He had a .45 in his hand and told him to shut the car off and open the door.

“The next thing he did was hit me in the face with the gun, which broke my nose,” Bowman recalled.

Then he heard the back passenger door open. He looked back and saw the guy with the multi-colored jacket getting back in. The man standing by the driver’s side window bashed him in the face again with his gun, breaking his nose a second time.

“Then the guy in the backseat put his gun to my head,” said Bowman.

He was told to exit the car, but when he tried to stall the would-be carjackers while haphazardly thinking of a way to escape with his car and his life intact, he took too long for their liking.

“I heard a loud ass bang and my ears started ringing,” Bowman said. “The bullet went in my head, came out and went through the middle finger of my hand that was holding the car keys. Blood was everywhere and I knew that I’d just been shot. The guy in the backseat jumped out and I began to panic, put the keys in the ignition, got the car in drive and peeled up outta there. I have no recollection of how I got there, but I was able to drive myself to Bon Secours Hospital, where I stumbled in and collapsed on the floor in the emergency room waiting area.”

***

The police later told him that they found more than 20 spent shell casings at the scene. When he woke up, he saw his wife and father crying.

“To see my son laying in that hospital bed was devastating,” said his father, Alvin Bowman Sr. “He’d been missing and we didn’t know where he was. As a father, I can’t even describe the pain of that moment, seeing my baby boy having to go through that.”

A physician told Bowman that in all his years working in a Baltimore City emergency room, this was the first time he was having a conversation with someone who’d come in after suffering a gunshot wound of that magnitude to the head.

“He told me if that bullet had gone an inch to the left or the right, that I’d be dead,” said Bowman.

“I was in Japan when Alvin got shot in Baltimore,” said his younger brother Aaron, a Morgan State University graduate and current engineer who works for the Navy designing ships. “We were all in shock wondering how this could happen. We knew he was struggling, no one had heard from him, but we didn’t think someone would try to kill him.”

According to the Maryland Opioid Command Center’s quarterly report released in June 2020, cocaine was the cause of the most non-opioid related deaths in recent years, meaning heroin, fentanyl, prescription opioids, benzodiazepines and methamphetamine weren’t the only drugs causing concerns in Baltimore and in the entire state.

According to the report, medical and treatment facilities noted that patients who combined opioids with non-opioids, with cocaine being the most used non-opioid, was unsettling. In 2020, 230 individuals lost their lives to cocaine use. This number was up by 15 percent from its 2019 count.

Maryland’s overall drug-related deaths were almost twice the national average, and that doesn’t even take into account the drug-related violence that has fueled Baltimore’s stupefying homicide rate.

“I wasn’t supposed to be a homeless, dirty, stinking crackhead that was living on the street, who was inches away from becoming yet another Baltimore homicide statistic,” said Bowman. “But there I was, laid up in a hospital bed with my head bandaged, feeling an intense sense of remorse and guilt as I looked at my father and my wife.”

Moments like that are what one might call, in addiction parlance, one’s “rock bottom”, the impetus to saying enough is enough before becoming determined to stop the insane roller coaster ride of drugs and self-destruction.

When his wife took him home from the hospital, he was still in those same church clothes from six weeks earlier. He smelled like hot garbage. She told him that he had to sleep on the inflatable mattress in the basement. He took a bath, stayed in bed and slept on and off for three days straight.

On the fourth day, while his wife was at work, he walked two miles through frigid temperatures to catch the #14 bus in Pasadena, which took him straight down Ritchie Highway and over the Severn River Bridge past the United States Naval Academy.

With his blood-stained head bandages and no cash in his pocket, he slowly ambled for close to a mile and into the Fourth Ward housing projects off Clay Street. He just knew that in the warped world where he existed, someone would see him and say, “A.J., what happened to you?”

“And I knew shortly after that, someone would give me some sympathy crack,” he said.

***

“There are people who are severely addicted to drugs like crack and opioids that don’t experience fear,” said Dr. Kenneth E. Leonard, Director of the Clinical and Research Institute on Addictions at the University of Buffalo. “It’s not unusual for people who are impulsive and either not fearful or don’t process the fear that they will not be deterred from using substances.

“And there are people who seek extreme experiences and sensations,” Leonard continued. “There’s a whole area of research around sensation seeking. Those people are more likely to try drugs and continue to move on into further drug use. For people that have severe drug addictions, all you can say is that the motivation for drugs becomes so enormous that rational thoughts about things like one’s health and safety or what your addiction is doing to everybody around you just doesn’t enter into the equation.”

Some people will ask, “Why didn’t Bowman just stop using drugs after the shooting incidents and stabbings, after bouts of homelessness, after numerous incarcerations, why did he continue with those destructive behaviors knowing what the tragic and morbid consequences were, and how they were not only negatively impacting him, but his family, friends and loved ones as well?”

After all, he was a bright young college graduate with a promising, lucrative career in the corporate realm, his future seemed pregnant with possibility.

But for people who are intimately familiar with the warped psychology of severe drug addictions and alcoholism – whether they themselves are actively using, are in recovery or have parents, family members, friends and loved ones who’ve succumbed to the darkness of the disease – the answer is somewhat simple.

The disease of addiction overwhelms them.

Those in the recovery community call it “Insanity”, which they define as doing the same things over and over again, expecting different results.

In the book, “Alcoholics Anonymous”, in the chapter titled, “There is a Solution,” the writer says on page 21, “Here is the fellow that has been puzzling you, especially in his lack of control. He does incredible, tragic things while drinking…He may be one of the finest fellows in the world. Yet let him drink for a day, and he becomes disgustingly, and even dangerously antisocial. He has a positive genius for getting tight at exactly the wrong moment, particularly when some important decision must be made or engagement kept.

“He is often perfectly sensible and well balanced concerning everything except liquor, but in that respect he is incredibly dishonest and selfish,” the writer continues. “He often possesses special abilities, skills and aptitudes, and has a promising career ahead of him. He uses those gifts to build up a bright outlook for his family and himself, and then pulls the structure down on his head by a senseless series of sprees.”

In the next chapter, “More About Alcoholism”, the writer says on page 30, “All of us felt that at times we were regaining control, but such intervals – usually brief – were inevitably followed by still less control, which led in time to pitiful and incomprehensible demoralization…Over considerable time we get worse, never better.”

In one of the seminal pieces written on alcoholism and addiction, “The Doctor’s Opinion”, written by Dr. William D. Silkworth and published in 1939, Silkworth writes, “We believe, and so suggested a few years ago, that the action of alcohol on these chronic alcoholics is a manifestation of an allergy; that the phenomenon of craving is limited to this class and never occurs in the average temperate drinker. These allergic types can never safely use alcohol in any form at all; and once having formed the habit and found they cannot break it, once having lost their self-confidence, their reliance upon things human, their problems pile up on them and become astonishingly difficult to solve.”

***

Bowman grew up in a middle-class neighborhood, on a tree-lined street with manicured lawns in the Annapolis area. His father was a lifelong Air Force veteran whose work at the Pentagon was classified. His mother was an elementary school teacher in Anne Arundel County.

Bowman was an exceptional student who regularly made the honor roll. In the area’s Pop Warner football and Little League baseball programs, he was a wunderkind. A quick running back with powerful legs and a slick-fielding, power switch-hitting third baseman, his father was proudly present at every sporting event.

“Alvin was an outstanding baseball player,” said Alvin Sr. “He had exceptional hand-eye coordination, was slick in the field and he could smack the leather off that ball. He had the potential to go really far in the game.”

But early on, there were some troubling signs of a sense of fearlessness that bordered on the foolish. One warm spring day when he was six years old, he decided to climb up on a dumpster and run around its edges. Losing his balance, he fell in and was severely cut by shards of glass. His injuries required over 30 stitches.

“I’ll never forget the doorbell ringing, and opening up the door to see Alvin Junior being carried and cradled in the arms of the fireman who pulled him from the dumpster,” said his mother Barbara Bowman. “There was blood everywhere. I was shocked and scared, but Alvin didn’t cry or seem the least bit concerned. He was scarily calm, like he wasn’t the least bit fazed.”

When he was a sixth grader at the Severn School, he was introduced to lacrosse. And the game immediately spoke to his soul. The speed, skills and acumen needed, the rugged nature of the fast pace and the toughness required to excel beckoned him.

“I was the only African-American kid out there,” he said, “but once I found out that NFL Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown was a four-time All-American lacrosse player at Syracuse, and that he was considered to be the best to ever play, I knew this game was for me.”

Severna Park is home to Maryland’s greatest high school lacrosse dynasty. On May 25, 2023, the Anne Arundel County powerhouse captured its 12th state championship, more than any other school in state history.

Bowman was one of only two freshmen to make the varsity lacrosse team in the spring of 1981. As a senior, he was an all-county running back on the football team. He ran indoor track in the winter and qualified to compete in four consecutive state championships. But it was on the lacrosse field where he truly dazzled.

“He was a very good running back for me who had a heart of gold, he could make some good things happen on the football field and he was an exceptional lacrosse athlete,” said long-time former Severna Park High School football coach and athletic director Andy Borland, who worked at the school from 1963 to 1998. “Inside of him was this huge, wonderful spirit. I knew his uncle and his dad and Alvin comes from a great family.”

Scholarship offers poured in from the likes of Duke, UMBC, Syracuse, Rutgers, Maryland and the Naval Academy, along with overtures from Ivy League schools Cornell, Yale and Princeton, among many others. He accepted an offer from the United States Military Academy, metonymically referred to as West Point.

“My father was a military man, and I came from a military family,” said Bowman.

The West Point coaches suggested that he take a post-grad year at the university’s prep school on the Fort Monmouth military base in New Jersey, reasoning that an extra year of training would better prepare him to dominate once he matriculated and began playing on the college level.

Four months into his prep school stay, he was hanging out in a parking lot with a group of other cadets who were sipping on beers. The cadet to his left lit a joint and handed it to him.

He’d never smoked weed before but decided to take a pull since everyone else seemed excited. As he exhaled, he passed the joint to someone who’d just walked up to the group and was standing at his right. Without looking at him, Bowman said, “This is awesome, you gotta try this!”

He didn’t realize it was an M.P., a military police officer.

“They told me I could either face a court martial or resign,” said Bowman. “So I resigned.”

All of the other cadets resigned as well, so they would not have to face a court martial and avoided having a dishonorable discharge on their records.

Having lost his scholarship, he decided to call all the schools that had once assiduously recruited him. He told them what happened at the West Point prep school. None of them were willing to offer him a second chance.

One of his best friends from high school, Rodney Long, who was playing soccer at Drexel University in Philadelphia, called and upon hearing Bowman’s story, spoke with the Drexel lacrosse coach.

“Alvin was one of the most energetic, resourceful and dynamic folks I’ve ever met, even to this day,” said Long, who lives outside of Chicago and manages an oncology practice for a pharmaceutical company. “He was someone who everyone knew and loved, with an ingratiating smile and laughter.”

The two had been buddies since their freshman year at Severna Park and had worked together through high school, earning money as grocery baggers at the PX store on the Fort Meade military base.

“The coaches at Drexel had been following me all through high school,” said Bowman. “Rodney talked to them on a Wednesday, the coach called me on Thursday and on Friday I went to visit the school. The next semester was set to begin that Monday. They offered me a full scholarship and by Monday, I had my dorm assignment, class schedule, books and my meal card.”

***

As Drexel’s lacrosse practices got underway, word soon spread about his athletic exploits. He was a starting midfielder as a freshman and by that point, well acclimated to the team’s culture of drinking and partying hard.

During one frat house party, while in an upstairs bedroom, Bowman recalls seeing someone measuring out cocaine and putting it in plastic baggies.

“I said, ‘Yo, lemme try that,’” Bowman recalls. “He gave me a line and I snorted it. It burned my nose, but I felt this immediate sensation. I went back down to the party feeling this incredible rush. And I learned that I could drink all night and not get drunk and could maintain this incredible energy if I was high on coke.”

After losing out on his West Point scholarship due to his first experimentation with drugs, one is tempted to again ask, why would he be so eager and desirous to try cocaine, a taboo substance that was frowned upon by most of society?

“Despite my academic achievements and my status as an elite athlete, and the fact that a lot of people admired and looked up to me, I had some self-esteem issues and always had this yearning to be accepted by the “in” crowd,” said Bowman. “I remember in high school when the rich kids’ parents were out of town and they’d throw these wild parties, they never invited me. I felt aggrieved and hurt behind that for a very long time. Weed and cocaine, in my opinion, was what the “cool kids” did and in a very warped way, me using those drugs made me feel a sense of acceptance in the beginning.”

Before long, Bowman had an open invite to that person’s room, and they would routinely hang out there drinking beer and snorting cocaine.

Bowman excelled on the lacrosse field and did well academically. He was named a team captain as a junior and senior. But drugs were becoming more and more prominent in his life.

“Alvin loved to party, but so did a lot of people in college,” said Bowman’s Drexel roommate and best friend Rodney Gillespie. “I knew that he was dabbling in cocaine when we were upperclassmen and thought it was just a once-every-now-and-then recreational thing with him. I never saw any severe signs that made me think he was an addict back then.”

Pictures of Bowman adorned the cover of Drexel’s sports media guide and posters of him hung in the cafeteria, but the duality of his diverging interests was becoming more pronounced.

Upon graduating in the spring of 1989 with a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration with a concentration in Management and Computer Information Systems, he stepped right into a well-paying management role with a pharmaceutical supply company and moved into a chic townhouse on South Street, one of Philadelphia’s most prominent and well known thoroughfares.

But the drug parties continued with more intensity after graduation, with Bowman soon dabbling in not only using cocaine but selling it in small quantities to those in his party circle as well.

Nattily attired in a navy-blue Armani suit, Bowman walked out of a sales meeting at a Berwyn, Pennsylvania restaurant on the evening of February 2nd, 1994, to sell drugs to an acquaintance who was accompanied by someone he’d met one time prior when he previously sold the duo a quarter ounce of coke. The stranger turned out to be a federal task force agent.

At the conclusion of his meeting, Bowman took the on-ramp to Route 202 South in the direction of Philadelphia. Within minutes, he was surrounded by a fleet of police cars, their sirens blaring and lights flashing.

“There were so many guns pointed at my head,” Bowman recalls.

The acquaintance, unbeknownst to Bowman, was an informant who painted a portrait to the Tredyffrin Township Drug Task Force of him being a major supplier and dealer.

Handcuffed and in a holding cell in the local Chester County police station, the questioning officer kept yelling, “Where’s the drugs, the guns and the money?”

Bowman feigned ignorance and when he was able to make a phone call, he reached out to a respected attorney who happened to be one of his most dependable coke clients.

Because he wasn’t in possession of any drugs or guns in his car, law enforcement had to release him on his own recognizance and could not execute a search warrant on his residence.

Within three hours, he was handed his charging papers and remembers reading the line, “Two hand-to-hand buys with an undercover agent…”

He was facing a potential prison sentence of 18 to 36 years.

***

Bowman got a sponsor and regularly attended 12-Step recovery meetings.

“That was just to help me out when I eventually went to court because I was still getting high and selling coke,” said Bowman.

His job, first wife and parents were unaware of the legal troubles and the daunting prison sentence he was facing. He continued with his double life as if nothing had happened.

While awaiting trial, Bowman was hanging out with one of his regular coke clients, a salesman from Boston who was in town a few times a month for work. The guy would normally buy his package and leave, but one night they got high together. Bowman laid out a few lines and was surprised when the man refused, saying, “I don’t sniff it. I cook it up.”

When he asked to try it, his client told him point blank, “Alvin, you don’t want to do this, man.”

Bowman persisted and was eventually passed a pipe.

“I felt like this huge, warm, comforting wave came over me, from the top of my head down to the bottom of my feet,” said Bowman. “My mind felt like it was expanding, the room felt more spacious, and I felt like I was elevating off the floor. It was an amazing feeling, like I was being taken away. That high supplanted any high I’d ever felt in my life. From there on out, I stopped sniffing as much and all I wanted to do was cook it up and smoke it. Crack was like a rocket that took me to another dimension.”

A few months after that first blast, he’d graduated to smoking it with more frequency, all while still awaiting trial. When his younger brother, Aaron, came to Philly to visit him for a few days, Bowman kept disappearing into the basement.

Curious, Aaron crept down the steps to see what his big brother was up to.

“WTF, dude!?” Aaron screeched when he saw Alvin, eyeballs bulging, lit pipe in hand. He immediately grabbed his stuff and drove back to Annapolis to tell his parents what he just saw.

“I was blown away when I saw my big brother smoking crack,” said Aaron. “I had no idea that he was a drug addict, and it broke my heart. I looked up to him all my life. He was my role model, and his lacrosse exploits back in Anne Arundel County were legendary. I played football and lacrosse in high school because I wanted to be just like him. To see your idol turn to dust in front of you was devastating.”

“I went back home a few days later and told my parents that I was in trouble,” said Bowman. “I told them that I’d been getting high and had gotten arrested, but they didn’t know the full scope of what I was facing until they walked into the courtroom with me.”

The gist of his court defense was that he’d never once been arrested or in legal trouble before, he was a first lieutenant in the military reserves who’d enlisted in June of 1989 (because he chose to resign from West Point rather than have a dishonorable discharge on his record, he was able to participate in ROTC in college and join the reserves after graduation) who was gainfully employed and a graduate of Drexel University.

“I don’t feel like you’re a menace or a waste,” Bowman remembers the judge telling him. “You can still do some good in this world, so I’m sentencing you to three years probation.”

***

For the next few years, Bowman was able to function at an extremely high level while limiting his drug usage to the weekends. With each new job came more income and more responsibility.

“People who are on stimulants, sometimes that helps them in their jobs for a while before things eventually collapse and fall apart,” said Dr. Leonard. “It’s not unusual to hear about people who are severely addicted that had periods of extreme production and accomplishment in the workplace.”

“I was a weekend drug warrior,” said Bowman. “Friday through Sunday was party time while the rest of the week I tried to keep things together.”

But things quickly spiraled out of control.

By 1999, after he finished up his probation term, he’d been arrested numerous times in Annapolis for drug possession and lost his high-paying corporate gig. He rebounded by landing a well-paying, sales director job in Northern New Jersey.

But he was fired within his first few weeks of working there after the back window of his company car was shattered in a shooting incident as he sped away from a dealer that he owed money to in Philadelphia.

He smoked crack through the night behind a dumpster, despite the bullet wounds to his right knee and foot that he’d sustained in the shooting. He was arrested the next day for possession of drug paraphernalia and taken to a hospital, where he was handcuffed to a bed. His bullet-riddled company car was immediately confiscated.

The charge was quickly dropped and he was allowed to leave the hospital after receiving medical attention, but the police had previously confiscated all of his clothes. In the middle of February, he walked out of there clad in only a hospital gown and socks.

He returned to the back of the dumpster where he slept and smoked crack for a few more days, panhandling to finance his habit.

A little boy cautiously approached him with a plate of food one day, saying, “I asked my mom if we could give you something to eat.”

Bowman, 32 years old at the time and ten years removed from his college graduation, began to cry.

He called his mother, collect, from the nearest pay phone, begging, pleading, “Mommy, come get me.”

***

Back in Annapolis, his parents put him out of the house after a few weeks when it became apparent that he was still using. He slept in the street or in an abandoned house if he could find one.

His aunt Fristine brought her car to a screeching halt one afternoon when she saw her disheveled nephew panhandling.

“Alvin Jr., you’re better than this!” she said with tears in her eyes.

After stringing together a few months of sobriety, Gillespie, his former college roommate who always supported him through his darkest of days, helped Bowman secure another well-paying job in the pharmaceutical industry where the company flew him to Durham, North Carolina weekly for sales meetings.

But on one of those trips to Durham, six months into the new gig, he disappeared into the abyss of another debilitating relapse for three months.

Gillespie knew that his friend had fallen off once again when he got a call from a colleague at the company where Bowman was working.

“Hey, Alvin was doing really great, but we haven’t seen or heard from him in two weeks,” Gillespie recalls being told. “I knew what that meant. I just continued to pray for him, hoping he’d find his way to the other side of that thing. My wife would ask me, ‘Why do you keep helping him?’ I told her that underneath it all, he was a good man who, despite his addiction, needed somebody in his corner.”

Bowman was eventually arrested for drug possession and spent the next year in prison.

“It tore me apart to see his life go in the direction that it did,” said Alvin Sr. “One of the officers who arrested him one time told me, ‘You’ve got a very intelligent, very smart kid there. He just has problems.’ All of the worrying and heartache, running up and down the road with him for lawyers visits, going back and forth to court and the times having to go pick him up from jail, all of that took a physical, mental and emotional toll on me. I got physically sick.”

“But I couldn’t turn my back on him,” Alvin Sr. continued. “We were going to stick by him, hoping that one day he’d get better. That’s what parents do, we suffer for our kids when they’re suffering.”

Seven years after being released from the Anne Arundel County Detention Center in June of 2002 after serving six months for yet another later arrest for possession of a controlled substance was when he was shot in the head in Baltimore in February 2009.

The gunman dressed in all-black was never found.

Nearly five years after the shooting, he decided he’d had enough and was desperate to get sober.

“I was back in Baltimore, hacking,” said Bowman. “That’s how I made my money to get high. I met this one guy who was a hitman that robbed drug dealers and I became his personal chauffeur for two weeks. He liked to get high too, so he’d tell me where to go, he’d jump out to rob a dealer and would come back with money and drugs.”

One day, after a substantial heist, Bowman’s mind began veering in a frightening direction it had never approached before.

“The guy always kept his gun within reach, and I started thinking, ‘If I kill him, I won’t have to share and can keep all of this crack to myself.’”

He was horrified when he quickly snapped back to reality. It was the first time that he ever thought of killing someone. When the hitman hopped out in search of another victim, Bowman sped away.

“I had eight dollars in my pocket, went into the Royal Farms over there by M&T Bank Stadium and bought a three-piece chicken dinner with fries and a biscuit,” Bowman said.

He called a previous sponsor, who asked, “You done yet?”

“Yeah, I’m done,” said Bowman. “What do I need to do?”

“Read page 30 of The Big Book and call me tomorrow,” the sponsor said before hanging up.

Page 30 of the publication Alcoholics Anonymous, commonly referred to by folks in recovery as the Big Book, is the beginning of the chapter entitled “More About Alcoholism.” The writer is specifically referring to alcohol and drinking, but Bowman substituted those terms with using drugs, specifically smoking crack.

“The idea that somehow, someday, he will control and enjoy his drinking is the great obsession of every abnormal drinker,” the author Bill W. writes. “The persistence of this illusion is astonishing. Many pursue it into the gates of insanity or death.”

The chapter ends with a call for the person in need of recovery to seek a higher power.

Bowman estimates that he’d been in and out of at least seven inpatient rehab facilities over the years and his previous attempts at sobriety never lasted for more than a few months. But something was different this time.

Bowman went to rehab and upon successfully completing the program, continued to seek treatment in an outpatient capacity, as well as regularly attending 12-step recovery meetings.

Earlier this month, on December 10th, 2024, he celebrated his ten year anniversary of being clean and sober. He currently serves as a sponsor to other men who seek what he currently has in his life – sobriety, peace, serenity, joy, contentment and a sense of purpose.

“It’s not unusual to hear about a person with a severe level of crack addiction taking multiple times in treatment before they get a lasting recovery, and that often involves both medical treatment and self-help,” said Dr. Leonard.

***

He’s been married to his third wife, Joy, for nine years. He had their spacious home in Laurel, Maryland built from the ground up a few years back. He’s currently one of the top commercial salesmen in the country for a national pest control company.

When he pops the trunk of his jet-black Mercedes Benz E53 AMG Coupe, with the custom designed interior made of premium black leather and a sound system that most nightclub owners would be jealous of, you’ll see what else he’s gained back with the lacrosse sticks, balls, gloves, helmets and padding strewn about.

“Alvin just recently shared his backstory with me and I was like, ‘How does that equate to the guy I know on the field?’”said Bowman’s Rusty Cannons teammate Joe Casalino. “It was like, wow, this guy pulled himself out of all of that. Hearing about what he’s gone through just brought a whole new level to the respect that I already had for him. Every single time we play he brings this awesome level of energy and enthusiasm. He’s always having fun and encouraging his teammates.”

“I watched him struggle for a long time,” said his brother Aaron. “He’d bounce back and dig himself out of these huge holes, only to fall down again. After a while, I stopped looking down on him and judging him because I came to understand the magnitude of this monster that he was battling. I began to admire him again because no matter how low he sank, he kept fighting to pull himself back up.

“I meet and spend time with some of the people who are in recovery with him,” Aaron continued. “And these are some of the most phenomenal people you’ll ever meet. I have a whole new perspective now about people who are struggling with that beast that is addiction. I no longer see them as weak. To get on the other side of where my brother and some of those folks have been requires incredible strength.”

After allowing his body to heal after his Harley Davidson squad captured the Grand Masters 55-and-Over championship at the Florida Lacrosse Classic in Fort Lauderdale over the Martin Luther King holiday weekend in January 2023, Bowman was back at it and re-energized. He kicked off that spring/summer season with his Rusty Cannons squad in the Maryland Masters Lacrosse League in March of last year.

That season ended on the evening of Thursday, July 27, at Troy Park in Elkridge, when the Cannons, despite the dangerously scorching heat, pulled out a 9-6 win over their main rivals, “Old And In The Way”.

The Cannons captured yet another championship in the Fall 2023 season, with Bowman tallying three goals and an assist in the title game against the Old And In The Way squad on November 9.

Prior to this previous Spring/Summer season, Bowman began taking Karate lessons to minimize the previous injuries that have taken away some of his effectiveness at times.

Bright and early on March 16, 2023, he was going through an arduous workout at the Okinawan Dojo in Ellicott City as a profusion of sweat ran from his shiny bald head and down his face as Anderson Paak and Schoolboy Q’s “Am I Wrong” blasted from the overhead speakers.

Anderson .Paak – Am I Wrong (feat. ScHoolboy Q)

He’s being pushed under the watchful eye of Sensei Stan Crump, a three-time world heavyweight Karate champion who has served as a personal trainer to the likes of NASCAR drivers Kyle Bush and Danica Patrick, among other professional athletes and celebrities.

“Right now, we’re working to strengthen his core muscles to increase his range of motion in his shoulders, hips, knees and ankles,” said Crump. “We’re starting to get his cardio better and we’ll soon begin to ramp up his strength training.”

Bowman’s 2024 spring/summer season with the Cannons ended on August 10 at the Ocean City Lacrosse Classic, a destination tournament in Ocean City, Maryland that hosts over 2,000 players across various divisions and annually doubles as a family vacation with his wife and step-daughter.

Trailing by a goal with less than two minutes to play that day, he sliced through the late afternoon humidity to corral a sweet behind-the-back pass from his teammate Jon Bang as he approached the crease. On the move, he caught the ball right handed as he motored toward the goalie. He faked a low shot and then unleashed a high right corner laser that landed in the net, forcing overtime.

The Cannons eventually lost in sudden death, 6-5.

With a strained Achilles that began bothering him during another tournament the week prior in Lake Placid, NY, Bowman gave his body a rest before the Howard County Recreation Master’s Lacrosse League’s fall season tipped off again in early September.

Under the lights at Troy Park in Elkridge, as the first cool fall temperatures descended on the area during the evening of Thursday, October 10, the Rusty Cannons ran their record to 5-0 with a 19-0 obliteration against a squad representing the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Bowman tallied three goals and an assist during the one-sided victory.

A few weeks later, he scored a goal in the championship game as the Rusty Cannons secured yet another title.

“Alvin is just a phenomenal young man, a wonderful teammate and everybody loves playing with him,” said the Rusty Cannons 76-year-old elder statesman Lenny Casalino, who notched two goals and an assist against the FCA squad..

A legendary figure in the state’s lacrosse community who played at the University of Maryland in the early ‘70s, Casalino is a former prosecutor who currently runs his own criminal law practice.

“If you just see Alvin walking around in a sweatsuit, you’d think he’s just this big guy,” said Casalino after the win against the FCA team. “But on the lacrosse field, he’s quick, strong and highly skilled. He can run fast in short spurts, can shoot with both hands and has exceptional vision. If I had to guard him, I’d tell one of my long-stick defenders, ‘Stay attached to that guy at all times. If he goes to the bathroom, you better go with him!’”

Bowman’s beyond happy to have the game that he loves, the game that formed the earliest inspiration and vision of where he wanted to go in life, as a part of his personal reclamation over these last ten years of sobriety.

“I’ve got lacrosse back in my life,” said Bowman. “Playing and winning gives me a sense of accomplishment. It helps me stay healthy, keeps me grounded and it’s a positive social activity. We might be fatter and slower, but the butterflies and excitement are the same as they were when I suited up in college.”

“And it helps me in my recovery because I have to be committed and accountable to myself and my teammates,” he continued. “Most people can look at old newspaper clippings and trophies, but I still have the game that helped me formulate my earliest dreams, and whenever I step on the field, it transports me back to a time in my life when everything was great, grand and groovy.”